Mind and Heart -- Warfield on Theological Studies and the Devotional Life

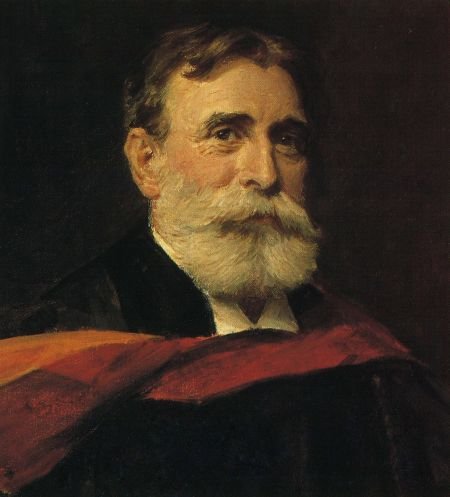

In October of 1911, B. B. Warfield delivered a conference lecture at Princeton Theological Seminary entitled The Religious Life of Theological Students. This has long been required reading for many Reformed and Presbyterian seminary students. But Warfield’s lecture should be read by church officers or anyone who reads a significant amount of theology. In fact, it should be read by all Christians who enjoy a life of the mind as well as embrace the biblical gospel.

Warfield’s lecture also serves as a corrective to the sort of Evangelical piety which eschews “head knowledge” for “heart knowledge,” as exemplified in a popular Calvary Chapel pastor who speaks of seminary education as “cemetery education,” since, he claims, this fills the mind with “doctrine not love.” Warfield’s essay is a wonderful counteractive to such nonsense, reminding all who heard his lecture then and read the text of it today, that for a Christian, mind and heart, while distinct, must never the separated.

Early in the lecture, Warfield makes the obvious observation . . .

Recruiting officers do not dispute whether it is better for soldiers to have a right leg or a left leg: soldiers should have both legs. Sometimes we hear it said that ten minutes on your knees will give you a truer, deeper, more operative knowledge of God than ten hours over your books. ‘What!’ is the appropriate response, ‘than ten hours over your books, on your knees’? Why should you turn from God when you turn to your books, or feel that you must turn from your books in order to turn to God? If learning and devotion are as antagonistic as that, then the intellectual life is in itself accursed and there can be no question of a religious life for a student, even of theology.

The mere fact that he is a student inhibits religion for him. That I am asked to speak to you on the religious life of the student of theology proceeds the recognition of the absurdity of such antitheses. You are students of theology; and just because you are students of theology, it is understood that you are religious men—especially religious men, to whom the cultivation of your religious life is a matter of the profoundest concern—of such concern that you will wish above all things to be warned of the dangers that may assail your religious life, and be pointed to the means by which you may strengthen and enlarge it. In your case there can be no ‘either—or’ here—either a student or a man of God. You must be both.

Warfield goes on to add,

Perhaps the intimacy of the relation between the work of a theological student and his religious life will nevertheless bear some emphasizing. Of course you do not think religion and study incompatible. But it is barely possible that there may be some among you who think of them too much apart—who are inclined to set their studies off to one side and their religious life off to the other side, and to fancy that what is given to the one is taken from the other. No mistake could be more gross. Religion does not take a man away from his work; it sends him to his work with an added quality of devotion.

The lectures is a gem of Reformed thought and piety, and I encourage you to read it in its entirety. You can find it here: Warfield: On the Religious Life of Theological Students